Qinghai Province

Introduction

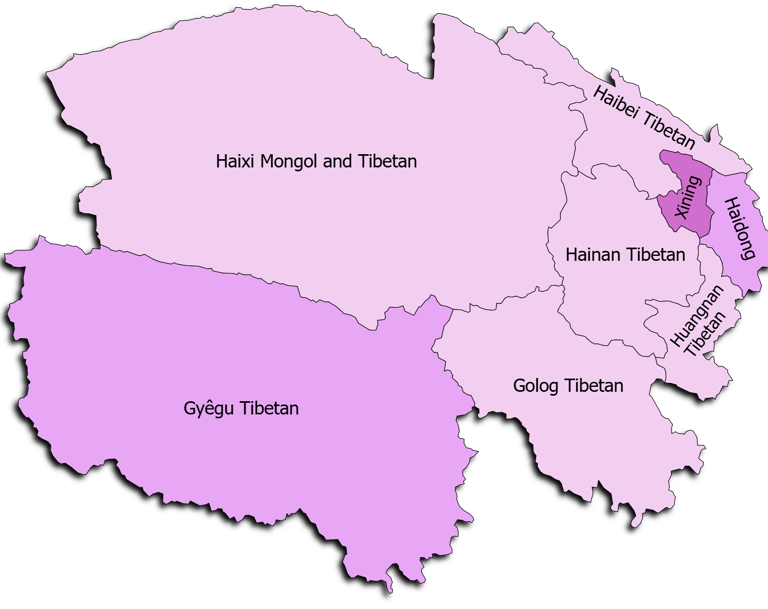

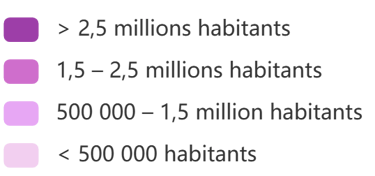

Qinghai Province, located on the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, stands among the highest and most remote regions of China. Home to around six million people, it is defined by vast grasslands, snow-covered peaks, salt lakes, and deep valleys, forming one of the country’s most striking natural landscapes. The province takes its name from Qinghai Lake, China’s largest inland lake, a symbol of both its ecology and its cultural identity.

Life here reflects a balance between Tibetan, Mongolian, Hui, and Han influences, where nomadic herding, monasteries, and modern towns coexist. Cities such as Xining, the provincial capital, and Golmud, a key hub on the Qinghai–Tibet Railway, serve as gateways across the plateau. Compared with eastern China’s dense urban regions, Qinghai feels open, quiet, and deeply connected to nature.

For centuries, this region has been a spiritual and ecological crossroads, linking Tibetan Buddhism, trade along the ancient Tea Horse Road, and modern environmental conservation efforts.

Geography and Key Cities

Qinghai is a land of high plateaus, mountain ranges, and vast lakes, where nature defines both geography and life. The province includes some of China’s most striking landscapes: Qinghai Lake, an immense saltwater lake surrounded by grasslands; the Kunlun Mountains, long considered a sacred range in Chinese mythology; and the Tanggula Mountains, which mark the border with Tibet and serve as the source of major Asian rivers such as the Yangtze and the Yellow River.

The capital, Xining, acts as the gateway between eastern China and the Tibetan Plateau, serving as a hub for transport, trade, and cultural exchange through its railways and highways.

Golmud lies deeper in the plateau and supports the extraction of salt, potash, and other minerals, while Delingha has become central to renewable energy and mining industries.

Yushu, known for its Tibetan monasteries and nomadic traditions, preserves much of the region’s spiritual and cultural heritage, and Haixi Prefecture stands out for its ethnic diversity and resource-rich deserts and basins.

Qinghai has a long and varied history. The region was significant during the Tibetan Empire and under the Qing dynasty, serving as a frontier for trade, religion, and pastoral nomadism. The area developed through Tibetan and Han cultural exchanges, as well as through the movement of traders and pilgrims across the plateau.

Throughout its history, Qinghai faced harsh climates, frontier conflicts, and cultural integration, with the Qinghai Lake basin shaping local livelihoods and traditions. In modern times, the province developed transportation, mining, and ecological conservation projects, balancing traditional nomadic life with modern infrastructure and tourism.

Historical Background

Nature and Landmarks

Qinghai brings together mountains, lakes, and open grasslands, forming one of China’s most visually and spiritually rich regions. At its heart lies Qinghai Lake, the country’s largest and most iconic lake, where migratory birds, herders, and Buddhist pilgrims converge every year. The surrounding Kunlun and Tanggula Mountains rise with snow-covered peaks and glaciers.

Among Qinghai’s most remarkable sights is the Chaka Salt Lake, famous for its mirror-like surface that reflects the sky and mountains. To the west, the Hoh Xil Nature Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site, protects rare wildlife such as Tibetan antelope, wild yaks, and snow leopards, representing one of the world’s highest and most fragile ecosystems.

Cultural and religious heritage remains equally significant. Kumbum Monastery near Xining, one of the six great monasteries of Tibetan Buddhism, and the temples of Yushu continue to serve as centers of spiritual life and pilgrimage. Across the grasslands and plateau villages, nomadic families still practice traditional herding, preserving ways of life adapted to the high altitude.

Culture and Cuisine

Qinghai’s culture mirrors its plateau geography and long history as a meeting point for Tibetan, Han, Mongol, Hui, and Salar communities. This diversity is visible in both daily life and architecture. Tibetan monasteries, Muslim mosques, and Mongolian-style yurts coexist with the modern buildings of Xining and Golmud, creating an environment where religion, ethnicity, and urban growth naturally intersect. Festivals and traditional arts remain central to cultural life. Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies, horse racing festivals, and yak herding rituals mark the rhythm of the year, while thangka painting, chanting, and dance preserve spiritual and artistic traditions rooted in the plateau.

The province is multilingual, with Mandarin, Tibetan, Mongolian, and Salar languages spoken across different areas, each maintaining its own heritage and customs. Thangka painting, wood carving, weaving, and folk music remain key art forms, often inspired by religion, nature, and nomadic life.

Cuisine in Qinghai reflects both the altitude and the pastoral economy. Food is simple, rich, and nourishing, centered on barley, yak meat, mutton, and dairy products. Common dishes include tsampa, the roasted barley flour eaten with tea or butter; yak butter tea, essential in daily life; grilled mutton skewers and steamed buns filled with meat or cheese; as well as fish from Qinghai Lake, often served dried or stewed. Yak yogurt and cheese are used in soups and snacks, while spicy hot pots help residents face the long winters.

Compared with the lowland provinces of eastern China, Qinghai’s food is heartier and more rustic, built around the needs of life on the plateau, where strength, warmth, and simplicity define both the cuisine and the culture.

Economy and Modern Development

Qinghai is an important ecological and resource-based province. Xining, Golmud, and Delingha developed into hubs for transport, mining, and energy projects during the 20th and 21st centuries, with salt, minerals, hydropower, and renewable energy forming the backbone of the economy. Tourism, especially around Qinghai Lake, Kumbum Monastery, and Chaka Salt Lake, also contributes significantly.

Historically, Qinghai’s economy grew from pastoral nomadism, trade along plateau routes, and religious pilgrimage, later expanding into mining, hydropower, and infrastructure. Despite geographic challenges, Qinghai maintains strong cultural and ecological traditions, balancing modern growth with preservation of nomadic life, sacred sites, and plateau environments.

Qinghai has produced influential figures in religion, scholarship, and local governance. Lamas, monks, and scholars from monasteries in Xining, Yushu, and surrounding areas contributed to Tibetan Buddhist thought and education. Local leaders and reformers supported pastoral livelihoods, resource development, and ethnic harmony.

The province is equally known for nomadic herders, religious practitioners, and ecological advocates, making Qinghai a spiritual, cultural, and environmental beacon. In modern times, Qinghai contributes scientists, conservationists, and cultural promoters who continue to embody its highland and plateau heritage.

People and Notable Figures

Current Trends and Daily Life

Daily life in Qinghai reflects the province’s balance between modern development and deep-rooted plateau traditions. In Xining, people work in education, energy, and public services, visit bustling markets, and enjoy an increasingly urban lifestyle, while on the grasslands and in mountain valleys, families continue herding yaks and sheep, practicing crafts, and maintaining Tibetan Buddhist customs.

Cultural and religious festivals remain key moments in the year. Horse racing gatherings, monastic ceremonies, and local fairs bring together nomads, farmers, and townspeople in celebrations that mix spirituality, music, and trade. The atmosphere of these events, set against vast open landscapes, highlights the province’s strong sense of community and continuity.

While Qinghai feels more remote and traditional than China’s coastal provinces, its role in renewable energy, tourism, and scientific research continues to grow. Solar farms, wind projects, and the Qinghai–Tibet Railway symbolize the province’s efforts to connect its ancient way of life with modern progress. Across the plateau, daily routines remain shaped by climate, altitude, and cultural heritage.

Practical Travel and Tips

Best time to visit: Summer and early autumn offer mild weather and blooming grasslands, spring is windy, and winter is cold with snow at high altitudes

Getting there: Xining is the main transport hub with railways, highways, and an airport, making Qinghai accessible from major Chinese cities

Highlights: Qinghai Lake, Kumbum Monastery, Chaka Salt Lake, Tanggula Mountains, Yushu Tibetan town, Hoh Xil Nature Reserve

Local etiquette: Respect religious customs, nomadic traditions, and high-altitude safety

Insider tip: Try tsampa and yak butter tea, explore lakeside grasslands, visit monasteries for cultural insight, and acclimate slowly to high altitudes.

Climate

Plant and animal life

Agriculture

Manufacture

Qinghai has a plateau continental climate, with cold, long winters and short, mild summers.

Summer temperatures rarely exceed 25°C in most areas, while winter temperatures often drop below −15°C, especially at higher altitudes.

Spring and autumn are brief, with large diurnal temperature variations. Compared with eastern provinces, Qinghai is drier, windier, and colder, reflecting its high elevation on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau.

The harsh climate shapes both human settlement patterns and nomadic grazing practices across the province, while high-altitude conditions affect agriculture and transportation.

Qinghai’s geography, from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau to high-altitude lakes such as Qinghai Lake, supports unique alpine and steppe ecosystems.

Grasslands and wetlands host yak, Tibetan antelope, wild asses, and various migratory birds including bar-headed geese. Alpine meadows and shrublands shelter medicinal plants, Tibetan herbs, and hardy grasses, while Qinghai Lake sustains freshwater fish and waterfowl.

Compared with lowland provinces, Qinghai’s flora and fauna are adapted to extreme cold, high UV exposure, and thin air. Seasonal migrations of wildlife and nomadic grazing patterns define the rhythm of life across the plateau.

Qinghai’s agriculture is limited by altitude and climate, focusing on cold-tolerant crops such as barley, wheat, and rapeseed in valleys, while pastoralism dominates on the grasslands.

Yak, sheep, and goat herding provide meat, milk, wool, and other products essential to local economies. Qinghai Lake and smaller rivers support limited freshwater fishing.

Compared with fertile eastern provinces, Qinghai emphasizes resilient crops and livestock suited to harsh, dry conditions.

Qinghai combines mineral extraction, energy production, and light industry. Salt, lithium, and rare earth minerals are mined across the province, while hydroelectric and solar energy projects leverage rivers and high-altitude sunlight.

Lighter manufacturing, including food processing and wool products, supports local communities. Tourism, especially around Qinghai Lake, Chaka Salt Lake, and Tibetan cultural sites, contributes to the economy.

Compared with provinces with diversified industrial bases, Qinghai’s economy is specialized but growing, balancing resource extraction, renewable energy, and cultural tourism, with ongoing investments aimed at improving infrastructure and connectivity with the rest of China.

Navigation

Main Menu

nathan.china-sphere.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.