Heilongjiang Province

Introduction

Stretching across China’s far northeast, Heilongjiang is a land of extremes—icy winters, fertile black soils, and a border defined by the Amur River. Roughly the size of France and home to about 31 million people, it is famous for its Russian influences, snow festivals, and vast forests. The name “Heilongjiang” literally means “Black Dragon River,” a reference to the mighty Amur that separates China from Russia.

Historically, this frontier province was home to Manchu, Oroqen, Hezhen, and other ethnic groups before being settled by waves of Han Chinese in the late Qing and Republican eras. Today, Heilongjiang is both a cultural crossroads and an industrial base, balancing modern agriculture and heavy industry with a distinctive identity shaped by its northern location.

Geography and Key Cities

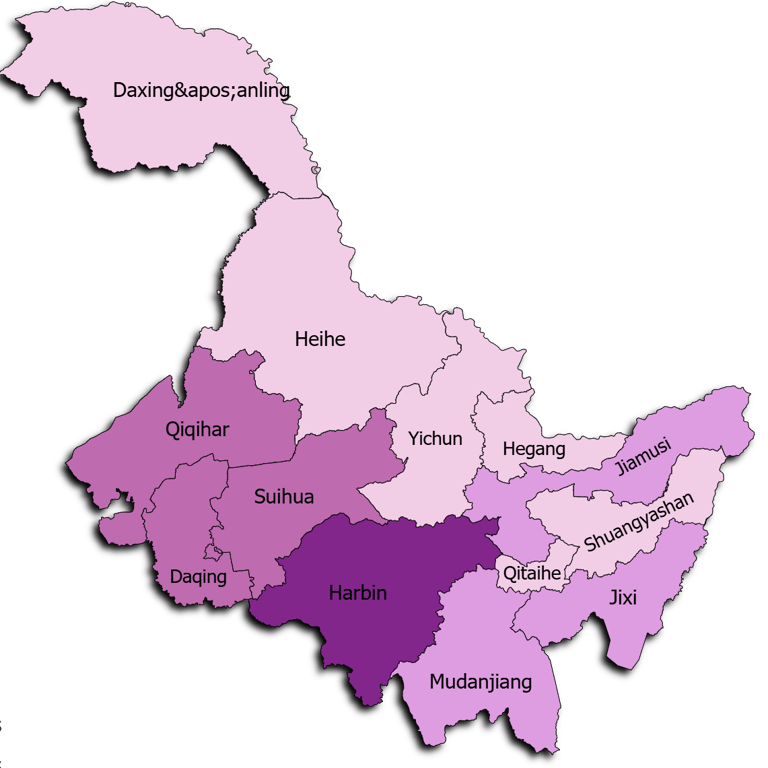

Heilongjiang is China’s northernmost province, bordered by Russia to the north and east, Jilin to the south, and Inner Mongolia to the west. Its landscapes are vast and varied: fertile plains along the Songhua River, dense forests in the Greater Khingan Range, and volcanic plateaus dotted with crater lakes. Winters are long, snowy, and severe, while summers are short but warm and productive.

Harbin, the provincial capital, is renowned for its Russian-influenced architecture and its world-famous International Ice and Snow Festival.

Qiqihar, the second-largest city, is an important industrial and cultural hub, known for nearby Zhalong Nature Reserve and its red-crowned cranes.

Mudanjiang lies close to Russia and Korea, serving as a gateway for cross-border trade. Jiamusi and Heihe sit on the Russian frontier, emphasizing the province’s transnational ties.

Yichun and Daxing’anling, deep in the forests, showcase Heilongjiang’s role as China’s timber and ecology frontier.

Heilongjiang’s history is shaped by its frontier location and resource wealth. In ancient times, it was inhabited by Tungusic and Mongolic peoples, and later integrated into the territories of the Liao, Jin, and Yuan dynasties. During the Qing dynasty, Heilongjiang served as a military governorate, guarding China’s northeastern borders and restricting Han migration to preserve strategic control.

With the decline of the Qing, waves of settlers transformed Heilongjiang into an agricultural heartland. In the early 20th century, Harbin became a cosmopolitan city along the Chinese Eastern Railway, attracting Russians, Jews, and Europeans who left an enduring architectural legacy. The region also endured turmoil during the Japanese occupation, when Heilongjiang was incorporated into Manchukuo and heavily exploited for its resources.

After 1949, Heilongjiang became a bastion of heavy industry, supplying coal, steel, and machinery to China’s modernization drive. Its role in border defense during the Cold War also reinforced its strategic importance. Today, Heilongjiang’s history remains visible in its architecture, industries, and cultural mix.

Historical Background

Nature and Landmarks

Heilongjiang’s natural landscapes are among the most dramatic in China. The Zhalong Nature Reserve near Qiqihar is a sanctuary for red-crowned cranes, one of East Asia’s most iconic species. Wudalianchi, a volcanic field of “Five Connected Lakes,” offers surreal black lava flows and mineral springs.

In Harbin, the Ice and Snow World transforms winter into an art form, with massive ice palaces glowing in neon light. Sun Island Park adds a summer counterpart with flower fields and riverside scenery. The Greater Khingan Mountains provide rugged wilderness for trekking and wildlife, while Jingpo Lake, China’s largest alpine lava-dammed lake, impresses with waterfalls and crystal waters. On the border, the Amur and Ussuri rivers form striking natural boundaries, with vistas of Russia just across the banks.

Heilongjiang’s landmarks highlight both nature’s raw power, volcanoes, rivers, forests, and the human creativity that thrives in a winter wonderland.

Culture and Cuisine

Heilongjiang’s culture reflects a mix of Han Chinese, Russian, and minority influences. Russian Orthodox churches, baroque architecture, and a history of Russian-speaking communities give Harbin a distinctly European flavor. Folk traditions of the Oroqen, Hezhen, and Daur peoples remain alive in music, crafts, and festivals tied to hunting, fishing, and river life.

Cultural life thrives in theater, music, and festivals, with Harbin’s Summer Music Festival being one of Asia’s oldest symphonic gatherings. Folk arts include paper-cutting, embroidery, and ice carving, a skill elevated into an art form during the snow festivals.

Cuisine is hearty and warming, designed for long winters. Wheat dominates over rice, with breads, dumplings, and noodles common. Russian-style breads and sausages are local staples, as are stews with potatoes, cabbage, and meat. Signature dishes include:

Guo Bao Rou: sweet-and-sour fried pork, Harbin’s most famous dish,

Harbin smoked sausage, a Russian-inspired delicacy,

Stewed chicken with mushrooms, reflecting forest produce,

Frozen pears and candied hawthorns, traditional winter snacks,

Beer culture, centered on Harbin Brewery, one of China’s oldest.

Compared with southern cuisines, Heilongjiang food is robust, meaty, and influenced by Russia, emphasizing warmth and sustenance.

Economy and Modern Development

Heilongjiang has long been an industrial giant, built on its coal mines, oil fields, and machinery production. Daqing Oilfield, discovered in 1959, remains one of China’s largest and a cornerstone of the national energy sector. Harbin specializes in equipment manufacturing, aerospace, and defense industries. Qiqihar remains a heavy-industry base producing railcars and machinery.

Agriculture also plays a central role. The province’s black soils make Heilongjiang China’s breadbasket for soybeans, maize, and wheat. Dairy farming, meat processing, and modern agribusiness have grown in recent decades. Forestry and timber industries, though historically important, are now balanced with conservation policies.

More recently, Heilongjiang has faced challenges of industrial decline and outmigration, but it is pivoting toward new opportunities. Tourism centered on snow, ice, and Russian culture is booming. Cross-border trade with Russia, renewable energy projects, and food exports are new growth drivers. Compared with coastal provinces, Heilongjiang remains less globalized but uniquely positioned as a bridge between China and the Russian Far East.

Heilongjiang has produced prominent political, cultural, and scientific figures. Among them is Wang Jinxi, the “Iron Man” of Daqing, celebrated as a model worker during China’s oil boom. The province is also home to renowned athletes in winter sports, including figure skaters, skiers, and ice hockey players, reflecting Heilongjiang’s role as China’s winter sports powerhouse.

Writers such as Xiao Hong, whose novel The Field of Life and Death portrays rural northeastern life, brought international attention to the region’s hardships and resilience. In music, the Harbin Symphony Orchestra stands as a cultural landmark with global connections.

Local heroes include conservationists protecting the red-crowned crane and the last surviving speakers of minority languages, embodying Heilongjiang’s cultural and ecological significance.

People and Notable Figures

Current Trends and Daily Life

Life in Heilongjiang is defined by its climate, industry, and borderland character. Urban centers like Harbin and Qiqihar buzz with universities, heavy industry, and a growing tourism economy, while smaller towns remain rooted in farming, forestry, and trade. Winters dominate daily rhythms, with ice skating, hotpot meals, and festivals central to community life. Summers, by contrast, are short but vibrant, with markets overflowing with fresh produce from the fertile plains.

Young people often migrate to Beijing or coastal provinces for work, but many remain to engage in tourism, agriculture, and cross-border commerce. Compared with coastal China, Heilongjiang feels slower-paced and more provincial, but it carries a strong sense of identity and resilience. Its Russian ties, music traditions, and ice culture give it a distinct northern flair.

Practical Travel and Tips

Best time to visit: Winter (December–February) for the Ice and Snow Festival, or late summer for cool weather and lush landscapes.

Getting there: Harbin Taiping International Airport connects to major Chinese and international cities. High-speed rail links Harbin to Beijing in under five hours. Domestic flights reach Qiqihar, Mudanjiang, and Jiamusi.

Highlights: Harbin Ice Festival, St. Sophia Cathedral, Sun Island Park, Zhalong Nature Reserve, Wudalianchi volcanoes, Jingpo Lake, and border towns like Heihe.

Local etiquette: Dress warmly in winter—temperatures can fall below –30°C. In rural areas, hospitality is generous; guests are often offered hearty meals and liquor.

Insider tip: Try frozen pears sold in Harbin’s winter markets, visit Wudalianchi’s volcanic hot springs in autumn, and attend the Harbin Summer Music Festival for a rare cultural experience in China’s northeast.

Climate

Plant and animal life

Agriculture

Manufacture

Heilongjiang has a cold temperate continental climate, defined by long, frigid winters and short, warm summers. Snow blankets the province for nearly half the year, with Harbin famously hosting the Ice and Snow Festival each January.

Winters are dry, with average temperatures in the north dropping below –20°C, while summers are mild and relatively humid, providing fertile conditions for crops. Spring arrives late and can be windy, while autumn is crisp and colorful, marking the harvest season.

Compared with other provinces climate, Heilongjiang is far colder and more extreme, with winter dominating daily life and culture.

Heilongjiang’s vast landscapes include fertile plains, dense forests, wetlands, and volcanic plateaus, supporting rich biodiversity.

The Greater and Lesser Khingan ranges are covered with larch, pine, and birch forests, home to sables, foxes, and Asiatic black bears. Wetlands such as the Zhalong Nature Reserve shelter migratory birds, especially the endangered red-crowned crane. Lakes like Jingpo host diverse fish species, while river valleys along the Amur nurture unique ecosystems shared with Russia.

Heilongjiang’s wildlife is more boreal, reflecting its northern latitude and forested wilderness.

Heilongjiang is China’s northern breadbasket, famed for its fertile black soils.

Wheat, corn, and soybeans dominate, with the province producing the bulk of China’s soybean harvest. Rice paddies flourish in the Sanjiang Plain, while dairy farming and meat production play key roles in the rural economy. Potatoes, sugar beets, and flax are also significant crops, reflecting the cool climate.

Forestry once provided timber, but conservation policies now restrict logging.

Heilongjiang specializes in large-scale grain and soybean farming, anchoring national food security.

Heilongjiang’s industry grew around its natural resources, with coal mining, oil extraction, and heavy machinery forming its economic backbone.

Daqing Oilfield remains one of China’s largest petroleum bases, while Harbin developed as a hub for aerospace, rail equipment, and defense manufacturing. Qiqihar contributes to machinery and railcar production, while Mudanjiang processes timber and food products.

Recently, the province has diversified into pharmaceuticals, renewable energy, and winter tourism.

Heilongjiang’s manufacturing remains resource-driven but increasingly linked to cross-border trade with Russia and new service industries.

Navigation

Main Menu

nathan.china-sphere.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.